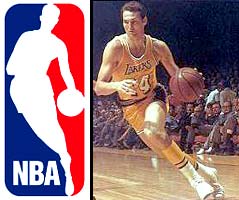

The NBA logo is, outside of the Olympic rings and the Nike "swoosh," the world's most recognizable sports emblem.

For years, players, fans and journalists have assumed that the figure depicted within the familiar NBA logo is Jerry West, the Los Angeles Lakers' Hall of Fame guard and the current president of basketball operations for the Memphis Grizzlies.

Search the Internet and you'll find sentences like this one, from Sports Illustrated staff writer L. Jon Wertheim in 2003: "(West is) well respected — no, lionized — in his field: one of the top 50 NBA players of all time, one so iconic that his silhouette adorns the NBA's logo."

The man who designed the NBA logo acknowledges that Jerry West is, indeed, Logoman. But the NBA is apparently reluctant to attach West's name to the silouette. (Photo illustration / FOXSports.com)

"It's Jerry West," Hall of Fame center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar told me recently. "I'm familiar with the original photograph from back in the '70s."

"My impression is that it's Jerry West dribbling to the hole," said David Kohler, president of Laguna Hills, Ca.-based Sports Card Plus Auctions and owner of perhaps the largest private collection of Lakers memorabilia. "I know it's always been assumed that it's Jerry West."

And yet, in a league with a well-deserved reputation for hyping even the most mundane milestone, the NBA did not celebrate the recent 35th anniversary of the logo's unveiling. The league has also refused to acknowledge publicly that West is the player in the logo. A high-ranking NBA official who asked that his name not be used told me that the identification of West is an "urban myth" and that the league has "no definitive records" about who designed the logo.

Why does the NBA refuse to admit that the logo is a representation of West? Is their "urban myth" statement PR bunk, or do they know something the rest of us don't?

The answer may lie within the mojo of the logo.

To many observers, the logo is a slam-dunk success. Designed by Alan Siegel and first unveiled in 1969, the image of a silhouetted player dribbling to the hole against a groovy red-and-blue background is ubiquitous: it appears on every uniform of every player, on every backboard in every NBA arena and on every piece of league-licensed merchandise, which generates a very groovy $3 billion in annual revenues.

To others, the logo is an anachronism. Today's players don't wear tight shorts; most don ultra-baggy uniforms and a great many of them have tattoos. In a league whose players are predominantly African-American and where so many of the players (despite race) relate to hip-hop music and/or its cultural significance, "Mr. Clutch" no longer seems to personify the on-court or off-court stylings of the NBA.

The logo, it appears, is stuck in the middle. Is it the ultimate badge of basketball excellence, as represented by a white player who was a perennial All-Star back in the day? Is it a timeless graphic-design icon that, after 35 years, can still serve as the public symbol for the league's global marketing campaigns, from Baja to Beirut to Beijing? Or is it as dated as the set shot?

As the NBA gathers in Houston for its annual All-Star Weekend extravaganza, the debate is getting fierce. New York Times columnist Selena Roberts recently wrote that the logo is "ancient" and that "(NBA commissioner David) Stern should update the logo."

Lakers head coach Phil Jackson disagrees with Roberts. "I like the logo we've got," Jackson explained. "It works fine. It's a flowing style that makes sense, whether it's Jerry West or not."

Logonomics 101

The premise behind any logo, of course, is that it represents a company's identity (in today's parlance, its "brand"). Through the 1950s, none of the "Big Three" professional sports leagues required a logo; sports were more about the games and less about the marketing of the games.

In the 1960s, the sports-business landscape began to change — and rapidly. Network television, and the millions of dollars generated by rights fees and advertising revenue, exerted a powerful force on team owners. The NFL supplanted baseball in popularity thanks to the marketing prowess of its young commissioner, Pete Rozelle, who created an in-house organization, NFL Properties, to license its merchandise — complete with a unique shield-like logo.

The NFL's patriotic-themed emblem signaled a unified, American league — and was very much a sign of the times. "Back then, in advertising circles, every product had to have an image — something with a picture — whether it was Betty Crocker or Tony the Tiger," recalled sports historian Bert Randolph Sugar, former director of marketing at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency.

The national pastime came next, with Major League Baseball unveiling its red-white-and-blue-silhouetted logo in 1968, just in time for the following year's celebration of the 100th anniversary of professional baseball.

Now, it was basketball's turn. Since its inception in 1946 (as, initially, the Basketball Association of America), the NBA had lagged behind the Big Two, a league in search of an identity. But in the 1960s, as integration opened up the doors of collegiate and professional sports, an influx of African-American talent, from Bill Russell to Wilt Chamberlain to Elgin Baylor to Oscar Robertson, energized the NBA.

Competition from the upstart ABA (in existence from 1967-1976) pushed the NBA; by the end of the 1960s and into the early '70s, with the title runs of the Knicks in New York's newly-opened Madison Square Garden, the three-martini lunch crowd along Madison Avenue's advertising row started to take notice.

With pro hoops poised to be the next big thing, Burbank, Ca.-based Licensing Corp. of America sold the NBA on the value of creating a recognizable trademark. The goal, remembers former Licensing Corp. president Joe Grant, was "to create an umbrella logo that tied together the merchandizing rights" for all of the NBA's teams.

Licensing Corp. hired Siegel, a New York City-based graphic designer who had previously directed the creation of the logo for Major League Baseball. Siegel has since become a well-known "branding and corporate identity" expert; his company, Siegel & Gale created the trademarks for, among many companies, MasterCard and 3M.

Siegel filled in the details in a recent telephone interview. Yes, he personally designed the NBA logo, for a fee of about $10,000, with help from a college buddy — renown sportswriter Dick Schaap.

"I found the original photograph in the archives of Sport Magazine (where Schaap later worked as editor in chief)," Siegel said. "It was an action shot of Jerry West dribbling down the court from one of the Lakers' games. I sketched it, cleaned it up a bit and stylized it. I streamlined the tracing I made — (and) slimmed it down a little bit — so it would work in all applications."

As for the color scheme, Siegel said, "We used red and blue against the white silhouette to create visual harmony with Major League Baseball's logo. I think I gave Licensing Corp. seven ideas, and (then-NBA commissioner) Walter Kennedy gravitated toward the direction that had the same look as Major League Baseball. I think he wanted to create the feeling that the NBA was part of the great American dream in sports — that the NBA was on the same footing as the national pastime."

Siegel credits illustrator Jerry Dior, who designed the Major League Baseball logo when the two men worked together at the Sandgren & Murtha agency, with creating the red-white-and-blue silhouetted motif. Today, Dior's design resonates beyond the NBA; the logos of the PGA Tour, U.S. Figure Skating and the National Lacrosse League, among others, emulate the design of the MLB logo.

The model player

Siegel said that he had no ulterior motive for selecting the photograph of West and that his main consideration was the image's aesthetics. Jerry West, however, was no ordinary player. The son of an electrician who labored for a West Virginia coal company, West joined the Lakers in 1960 after helping the U.S. win an Olympic gold medal at the Rome Olympics. With sidekick Baylor, West practically invented pro basketball on the West Coast. His all-around play earned him annual trips to the All-Star game (including MVP honors in 1972 on his home court, The Forum in Inglewood).

"He's one of the greatest players that's ever stepped on the court," said Abdul-Jabbar, who played against West when he entered the NBA with the Milwaukee Bucks. "Clutch shooter, great heart, played the game at both ends of the floor."

Many consider West's competitiveness to be his greatest attribute. During the 1960s and early 1970s, the Lakers reached the NBA Finals an astounding seven times, and lost every time. West never gave up on winning a championship until, finally, the Lakers prevailed over the Knicks in 1972.

After his retirement, West served three seasons as the Lakers' coach before transitioning to the front office, eventually running the Lakers' basketball operations from 1982 to 2000, and winning praise for building four championship teams. He was hired to guide the Memphis Grizzlies' basketball fortunes in 2002.

"He's a class act," Sports Card's Kohler said. "For the NBA, he is a symbol of excellence."

His identity as the figure in the logo is perhaps the worst-kept secret in sports. In 2000, the Boston Globe's Bob Ryan wrote: "It is not exactly privileged information that the silhouette of a player comprising the official NBA logo is that of Jerry West, a man who resides in the inner sanctum where only the truly great players in NBA history can claim a spot."

On the Basketball Hall of Fame web site, the biography of West includes this sentence: "His image is silhouetted in the NBA logo."

Over the years, however, the NBA has refused to recognize publicly that West is the player in the logo. When I repeated to Siegel the NBA's claim that the identification of West is "an urban myth," he bristled. "That's bull----," he said. "I guarantee you that it's Jerry West."

When I contacted West at his Memphis office, he was reluctant to talk about himself or the logo. "If it is me, I'm obviously honored that they would have thought enough of me to place me there. But I don't think they've ever officially confirmed that it's me."

He acknowledged that he has a copy of a photograph that shows him dribbling against former Atlanta Hawks star Joe Caldwell at the Fabulous Forum in Inglewood. West said that his body positioning in the photograph is identical with the logo. (He also believes that Wen Roberts, the Lakers' longtime team photographer, may have taken the photo.)

Asked about the league's position, West said, "There's been so many great players in the NBA, they don't want to offend anyone. They don't want to single out anyone. If that's me, I'm proud of it. It's served them well for a number of years."

When I asked him if the NBA might have a financial motive for refusing to identify him — that he might be entitled to royalties for the use of his likeness — West chortled. "You publish this story and I'll call (my agent) and find out," he joked.

A league reborn

The West-ified logo made its first public appearance in the fall of 1969, on the cover of that season's "NBA Guide," the statistical reference book published annually by the league. The logo also appeared on players' uniforms the next season, to mark the 25th anniversary of the league, before disappearing from view for a decade.

When the logo next appeared on the "NBA Guide," before the 1979-80 season, the bright promise the NBA had built up during the 1960s and early '70s had almost disappeared. Rumors ran rampant that many of the NBA's players were drug users. The NBA Finals were not broadcast on live TV, but shown on tape-delay near midnight. And, while the merger with the rival ABA in 1976 had infused the league with talent, pro hoops faced an image problem.

The perception, as former CBS announcer Dick Stockton once told me, was that the NBA was "too black." As a die-hard sports fan growing up in New York City, I well remember those times. During the late 1970s, when the Knicks fielded an all-black roster, they were derisively referred to with a nickname containing the "N" word.

At the NBA's darkest hour came salvation, in the forms of Larry and Magic and Michael and David. The transformation began with Larry Bird and Earvin "Magic" Johnson joining the Boston Celtics and Los Angeles Lakers, respectively, and setting up a cross-country rivalry that highlighted exquisite, unselfish team ball. They were soon joined on the court by the Chicago Bulls' Michael Jordan, whose winning ways were augmented by a Spike Lee-directed advertising campaign for sneaker-behemoth Nike that turned him into the world's most recognizable and marketable sports star.

Away from the court, David Stern replaced Lawrence O'Brien as league commissioner in 1984. Stern ramped up the NBA's marketing efforts and took advantage of new technology that spread the game — via satellite television and, later, the Internet — to distant lands. "I Love This Game!" became a mantra that didn't need a translator, especially after the league unleashed the dominant "Dream Team" at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics.

One of Stern's most subtle, but shrewdest, acts was to revive the logo. It returned to players' uniforms during the 1986-87 season and became an important symbol for the revitalized game. Revenue soared as the league mined new trends (video games and movies, cable television, "throwback" jerseys, corporate alliances). The global marketing strategy paid dividends beyond merchandise sales as talented foreigners made the NBA their destination. From Germany came Dirk Nowitzki, from Argentina came Manu Ginobili, and from China came the biggest prize of them all: Yao Ming.

"As commissioner Stern brought his marketing skills to bear, the NBA went from being mildly popular in the early 1980s to becoming the worldwide commodity it is today — an identifiable American brand as visible as Starbucks and McDonald's," said USC professor of cinema Todd Boyd, author of "Young, Black, Rich and Famous: The Rise of the NBA, the Hip-Hop Invasion and the Transformation of American Culture."

The next generation?

Even as NBA coffers filled with dollars, marks and yen, trouble was brewing in paradise. Bird, Johnson and Jordan gave way to the next generation, and the NBA's core product — the game of basketball — appeared to suffer. As journalist Michael Sokolove wrote in the New York Times, the players are "so young, so green, so unschooled (four years of college is now exceedingly rare), and so raised on a diet of ESPN highlights that many have nothing but so-called N.B.A. bodies. Unbelievable as it may seem, you can make millions in today's NBA without having even one semi-reliable way to put the ball in the basket — no jump shot, no hook shot, no little 12-foot bank shot."

Further trouble came in 2004, when the U.S. team comprised of NBA stars was humbled at the Athens Olympics and took home "just" a bronze medal. And then, the proverbial last straw: the brawl at Auburn Hills last season, when Indianapolis Pacers guard Ron Artest charged into the stands and fought with fans after being pelted by a beer.

The incident was a public relations disaster for the NBA and fueled a backlash. League executives, who had previously encouraged the marriage of hoops and hip-hop, now worked to distance themselves from what some perceive to be its image. Stern pushed through rules that raised the players' minimum age to 19 and instituted a dress code, both on-court (uniforms must not droop lower than the kneecap) and off-court (no doo-rags and oversized jewelry while at the arena).

These measures may or may not repair relations between players and fans. But they suggest that the NBA, for all its success, finds itself in the midst of an identity crisis. And, that begs the questions: does the present logo represent today's brand of the NBA? If not, should the NBA retire it and bring in a sub?

Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban thinks that the logo works fine, but he says the league needs to improve its marketing efforts. "(The logo) represents the NBA, but it's how you enable the brand that matters, not the logo itself," he said. "It's a much more competitive environment (today), and we've got to work harder at it. Unless we have a good marketing program, the logo is irrelevant."

"I think this is a business decision for the corporate thinkers in the NBA," said Richard Lapchick, founder and director emeritus of the Center for the Study of Sport in Society at Northeastern University. "They have to figure out if it would be better to change the logo to make it more reflective of the league's players or to keep the logo that has such a rich history. The big qualifier with this is that the NBA has such a progressive record regarding its racial hiring practices in terms of who runs the game — head coaches, team presidents, even owners."

Said designer Siegel: "I wouldn't change it. I wouldn't try to modernize it. I wouldn't put longer pants on it. It's an iconic symbol that represents a classic presentation of basketball."

West says, "It doesn't bother me at all (if the NBA updates the logo). But there's so many great players that have played over the years — Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Michael Jordan. I don't know how they (could) decide."

Lakers forward Lamar Odom believes that "some things are meant to stay the same. Yet, there's always time for change. If you want to put someone on a logo, as far as the impact and what they've done in the league, there's probably only one person you should put on that logo: Michael Jordan."

But a quipping Phil Jackson said, "Update it to what? A guy carrying the ball instead of dribbling the basketball?"

Ultimately, standing pat with the current logo reflects sound business principles. To alter the trademark would signify major panic in the NBA's marketing strategy. The NBA needs some tweaking (have you seen how much tickets cost these days?), but it doesn't need a new identity. Besides, Odom's suggestion for the best candidate to sub for West, Jordan, already has his own personal logo: the "Airman," designed from an image of one of his spectacular dunks and used on Nike and Air Jordan products.

There's a third route the NBA could take: retain the traditional logo on uniforms and in arenas, but introduce a new one for other uses (say, video games). It's a compromise that could backfire (can you say New Coke?). But with two logos, the league could retain the value of the historic logo and have another for Generation Next.

The NBA has some experience in this: when the league created the offshoot WNBA in 1997, a feminized logo was introduced that echoed the NBA logo. Most recently, the logo for the NBA Development League was designed to resemble the original.

The league should come clean and admit that West is the player in its logo and honor the fact that its public symbol is also one of its upstanding citizens.

The NBA should honor its connection to the past that, not so long ago, helped launch pro hoops into the modern era. The logo is NBA basketball, and the league should celebrate that.

Thanks to David Davis at FOXSports.com.