Most people who have bought any musical recordings over the past 60 years might have assumed they always came in covers, or sleeves, or jackets, that featured a colorful graphic designed to enhance the lure of the music.

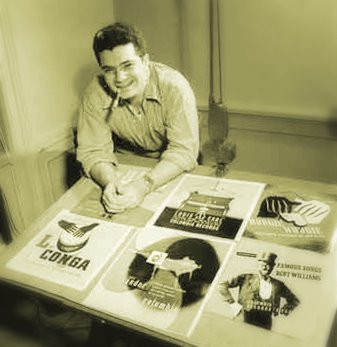

They didn't. Album covers had to be invented. This was a task that largely fell to a Brooklyn kid named Alex Steinweiss.

Before Steinweiss entered the business in the 1930s, most 78-rpm records, the only kind that existed, were sold in plain brown sleeves, flimsy pieces of paper with a large round cutout so the label would show through. If the record company was ambitious, it might list other releases on the paper, as a kind of promotional afterthought.

This changed slightly around 1935, when record companies began bundling several 78-rpm discs in one package, with a cardboard outer jacket. An "album," this was called. But even then, to keep costs down, companies would mostly just stamp the name of the artist on the front.

Then in 1939, Columbia Records hired Steinweiss, a 22-year-old design whiz kid, to become its art department.

Technically, Steinweiss would recount in his 2000 autobiography, "For The Record," that he was hired to create catchy ads and promotional posters for store displays. But he had his eye elsewhere. The company was wasting its greatest promotional opportunity, he argued, by blandly stamping a name on the front of albums. They looked like tombstones, he said. Why not make 'em sing?

So he invented the album cover.

His bosses liked his designs from his very first project, a Rodgers and Hart collection. But what sold them wasn't art, it was numbers. After he redesigned the cover for an album of Beethoven's Ninth, sales rose 894% in six months.

That won him the green light to create cover designs for everything from Bartok to Broadway to Bessie Smith.

His designs were influenced by the art schools with which he had worked, but they were also his own: stylized images with clean lines and bold colors that often exaggerated some feature to highlight what Steinweiss, himself a deep fan, felt was the essence of the music.

For an album of boogie-woogie piano, he drew a keyboard played by two huge hands, one black and one white - a subtle but unmistakable acknowledgment that boogie-woogie brought together both sides of a racially divided country.

For a Kostelanetz recording of George Gershwin's "Rhapsody In Blue," he drew a small piano under a small street lamp, with a huge silhouette of a city skyline towering behind.

He did all this, moreover, with tools that were as primitive as 78-rpm records. Steinweiss worked with rulers, T-squares, pencils, paste and glue on a drawing table. He could use photographs only sparingly because they were expensive to reproduce, and printing technology severely limited his color palette.

But he didn't care. He knew exactly what he was doing because he'd been working up to doing it all his life.

Steinweiss was born March 24, 1917, on the lower East Side, the son of Eastern European immigrants who moved to Brooklyn when his father, Max, became established as a women's shoe designer and mother Betty as a seamstress. Max immersed young Alex in opera and classical music and in 1930 he enrolled at Abraham Lincoln High, where his visual-arts teacher was Leon Friend, a key figure in galvanizing a generation of graphic designers who would one day define the look of everything from pop culture to advertising.

Friend's students were known as "The Art Squad," and after Steinweiss graduated from Lincoln and then Parsons, he became one of the bright lights. He worked under various design stars and became somewhat well-known, though hardly rich. By the late 1930s, he was making just $30 a week, barely enough to support himself and his new bride, Blanche Wisnipolsky, whom he married in 1938 after a six-year courtship that began when they met at Brighton Beach.

Columbia hired Steinweiss as part of a bold marketing push that included selling 78-rpm albums for $1 instead of $2. Steinweiss' bold designs, the label hoped, would get this campaign noticed.

It did, though he soon turned his brush to a more-urgent cause: winning World War II. After he enlisted, the Navy decided he would be more valuable behind an art table than an anti-aircraft gun and he spent the war in New York turning out informational and morale-boosting posters.

One showed a group of black Navy recruits with the message: "Advance through training: Skill commands respect." Another said: "Hands off the Americas," and showed the body of a bloody-handed Nazi hanging from a scaffold.

When Steinweiss returned to Columbia after the war, engineers were finishing up the development of 331/3-rpm records, which soon would be sold in 12-inch jackets, which for his purposes simply meant a bigger canvas.

By now, every label had followed Columbia's lead and given their albums designed covers. Steinweiss began to freelance, and in 1954 he left Columbia. He worked in music, advertising, magazines and other design areas before retiring in 1972 to concentrate on his own art.

He was still around when album covers were downsized to compact disk and cassette covers, which he and other connoisseurs felt negated much of the impact. But, meanwhile, it helped build and sell the modern music biz.

You can find more info on Steinweiss here as well as this sweet little flash presentation from the Eisner Museum

Thanks to David Hinckley for help with the above.

That's Right,

HMK

No comments:

Post a Comment